Article and photos by Oliver Child (University of Bristol)

This January, I was fortunate to trade the worst of the British winter for the much milder climate of southern China. I wasn’t there for the weather (although that was a plus), but to join the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Research at Scale Residency to explore the exciting manufacturing and electronics ecosystems of Shenzhen and the surrounding Greater Bay Area.

Along with the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech), AIRS, Seeed Studio, and students from MIT, I had the chance to explore the electronics markets, visit factories, understand the city, and meet the most amazing people. This was a chance for me to put my research in personal fabrication into the context of the larger global manufacturing system.

My visit was supported by pro2 (‘prosquared’), a UK Research and Innovation funded network which aims to democratise digital device production. A single post wouldn’t be enough to convey all the interesting things I discovered on this trip or how blown away I was with everything I saw, but here are some highlights!

Presenting Printegrated Circuits at the Scalable HCI Symposium

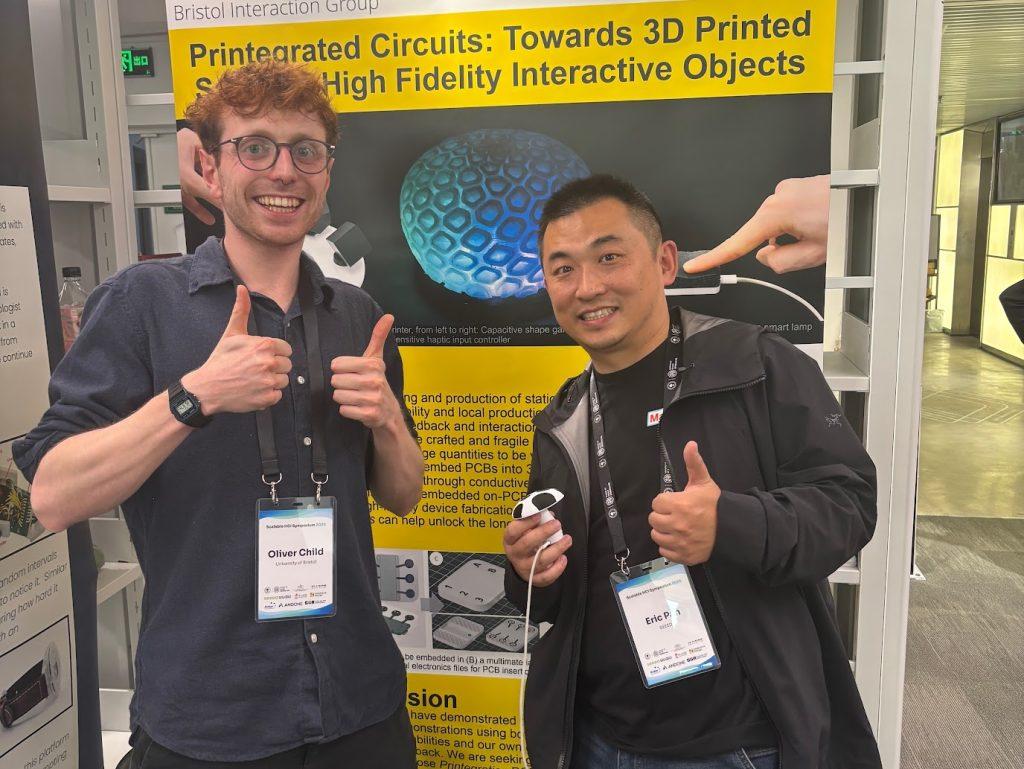

Thanks to the amazing work of the organisers, Scalable HCI welcomed researchers from across the world interested in making hardware in HCI. The opportunity offered me the chance to present my ongoing work around developing scalable prototypes with 3D printing processes to other researchers, as well as international innovators in device manufacturing.

I brought along some demos including the TuneShroom, an almost fully 3D printed midi controller in the shape of a mushroom. Getting feedback from other attendees was invaluable, especially from Eric Pan, the CEO of Seeed Studio. Eric has many years’ experience developing and deploying devices to hobbyists as well as commercial customers, all from Seeed’s local headquarters in Shenzhen.

Meeting Eric Pan, CEO of Seeed Studio

Tangible Explorations in Huaqiang Bei

Having so much of one industry in close proximity is fertile ground for developing amazing places like the electronics markets in Huaqiang Bei. They offer a sprawling collection of specialised malls filled with booths selling all kinds of electronics components, tools, prototyping kits, and fully fledged devices. Having visited Shenzhen previously in 2019, I could tell the markets had experienced some decline, but it was encouraging to see so much in-person exchange still existed in such a digitally connected society.

The value of the markets comes from a tangibility you can’t get online. You can physically browse rather than relying on filters and product categories like those offered by Digikey or Farnell. You can feel every switch, pogo pin, or membrane pad, and see the true colour of the LEDs, displays, and cases. You can also talk directly – or in my case via a translation app – with the manufacturers, who can explain their processes and say where and how customisation is possible.

I liked this stall that was representing a factory that made membrane interfaces.

Shanzhai, Gongban and Alternative Open Realities

There was also a range fully assembled devices, primarily mobile phones and other screen-based devices, many of which are what is known as “Shanzhai” (山寨), or variations on existing devices with extra functionality. My favourite were the tiny iPhones running a re-skinned android. Some people call these counterfeit devices, but really they are a unique product in their own right but with a market so small they can only thrive somewhere where short-run production can support them.

Silvia Lindtner is someone who has spent a huge amount of time studying the Shenzhen ecosystem and explains in her work that shanzhai devices are based around “Gongban” ( 公 版) or “public boards”. Essentially, they are freely available designs of boards for different applications that component suppliers offer up – like a reference design with features – that manufacturers are able to make, but in doing so will buy components from the component manufacturer. The creativity lies in how people re-mix these designs and make custom shells for them. Different IP laws and structures make this kind of crafting in production possible.

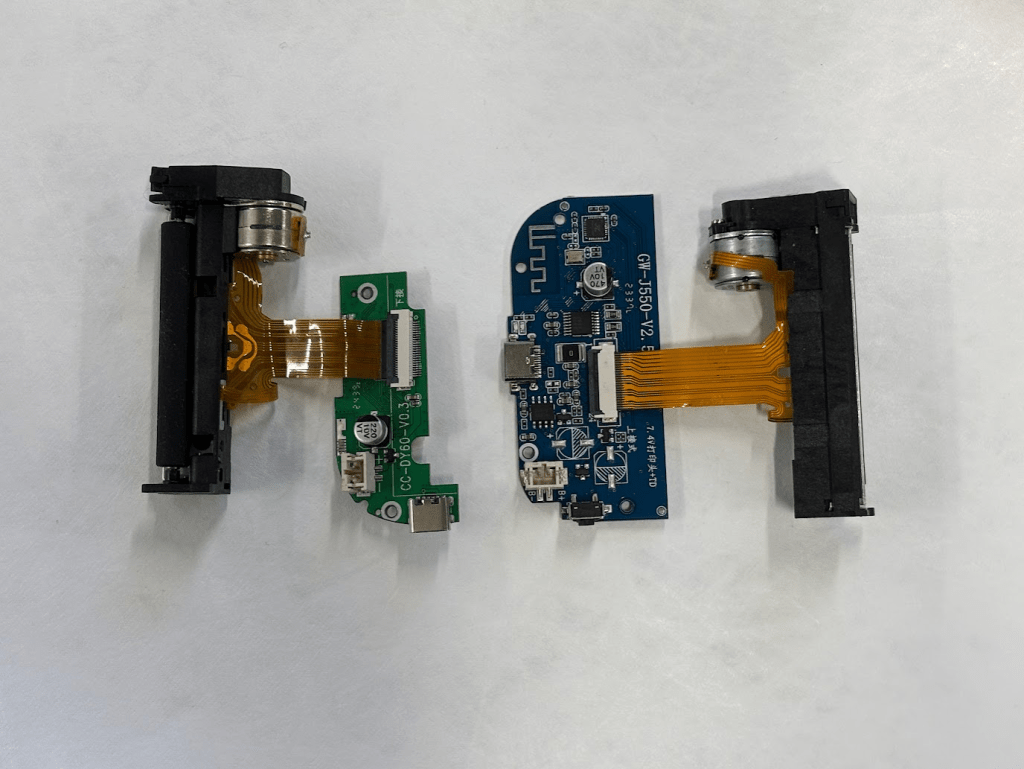

One other device that caught my eye were the camera + receipt printer combos. They were being sold everywhere, but weren’t the same product. They all had different shells and enclosures, some had screens, some were just printers, and some were just cameras. This kind of variation in such a small product was intriguing. Just like the highly specialised shanzhai phones, I was curious how these devices were so refined, but for such a niche market.

I bought a couple models of the camera-less Bluetooth toy printers to see the insides. While similar and based around a different MCU both a JieLi Bluetooth controller, they weren’t the same. I wonder if one was a newer vs older version.

Phone Repair Markets and Unmaking in the Wild

Across the street from the electronics components markets was the communications building, focused solely on second hand phones and phone repair. The ground floor tool shops offered jigs and stencils to remove and re-ball the BGAs from each model of phone’s motherboard, and higher levels had bags of components from FPCs to camera modules to individual chips.

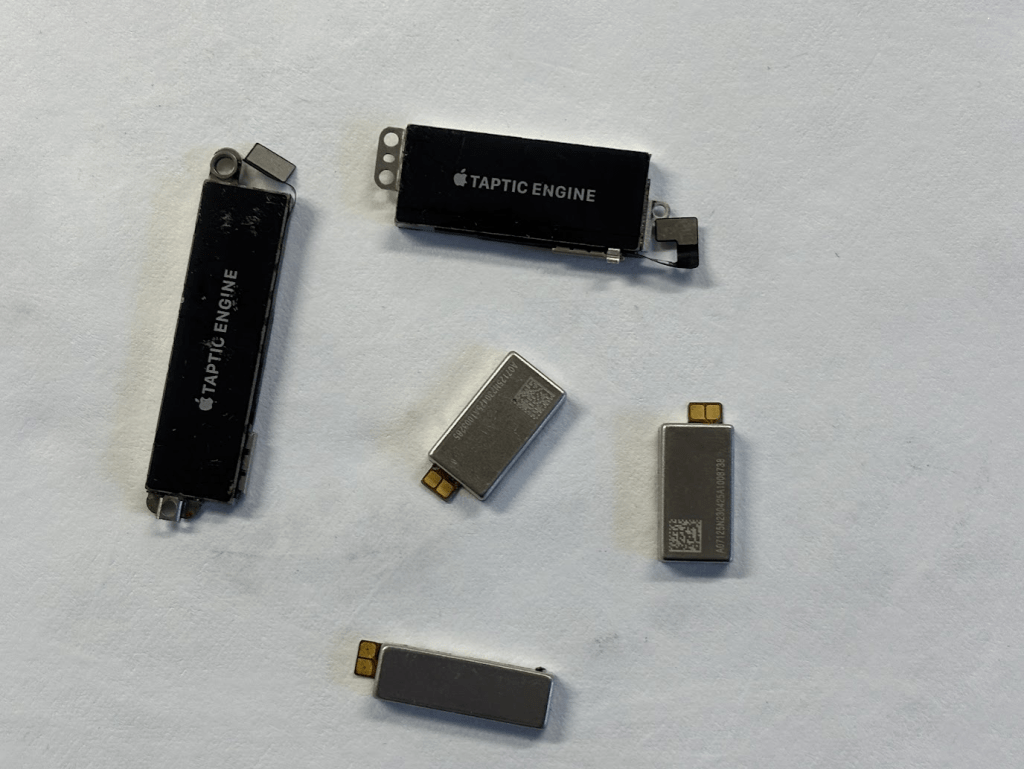

I was in search of Linear Resonant Actuators (LRAs) to add tactile feedback to my Printegrated Circuit devices. LRAs are the replacement of dumb vibration motors that allow modern phones to create different vibrotactile responses to user input. After a bit of searching, we uncovered a range of different options that had been recovered from old phones. I was able to pick up the Taptic Engine from several iPhone variants as well as some Xiaomi phone’s LRAs, each costing 1 RMB or about 15 cents.

I find it interesting that in HCI research, desoldering components or the repair and building of Frankenstein devices is presented as a speculative future or impossible ideal, whereas in Shenzhen the density of parts, expertise, and skill makes it a reality.

Factory Visits

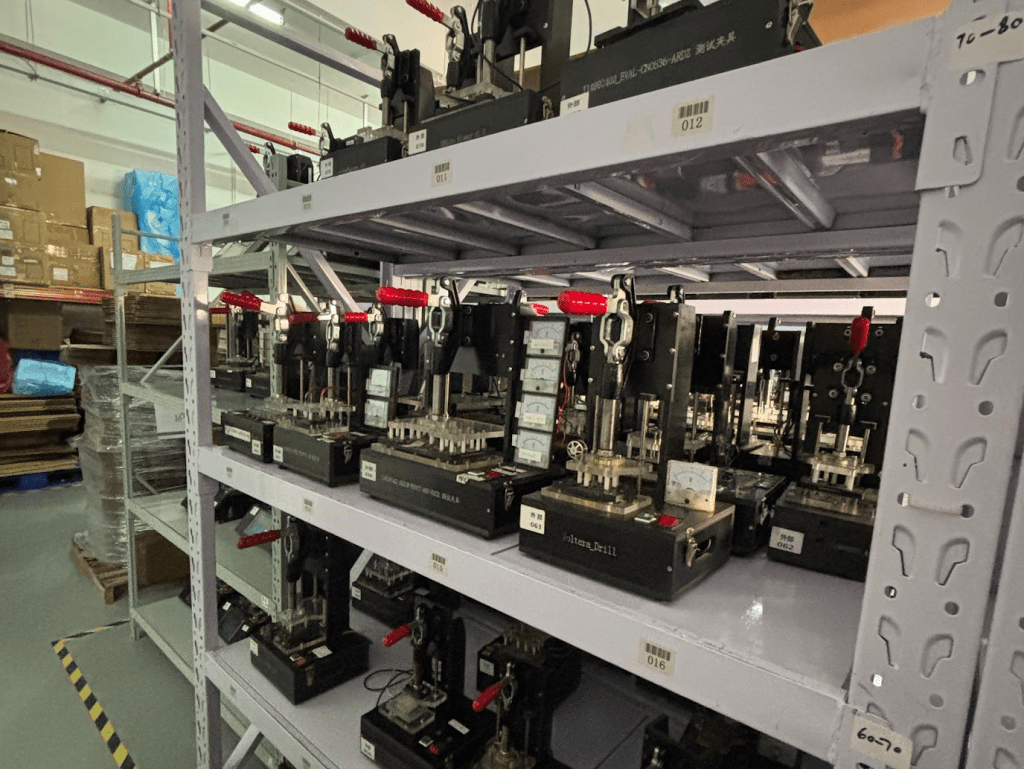

I also visited a number of electronics, moulding, and display factories with the other symposium attendees and residents. What struck me was encountering some of the fastest machines I’ve ever seen along with similarly impressive levels of manual assembly. It was explained to us that in many cases it is not worthwhile setting up machines for short runs when human labour is so flexible.

Testing and verification was done with testing jigs as well as by human eye.

The Shenzhen ecosystem is not only capitalising on scaling up, but also the capabilities of rapid prototyping of one-off parts.

This room filled with around 40 industrial resin printers was a new addition to an injection moulding factory as it tried to target the market of mass customisation and product prototyping.

Research At SUSTech & Seeed Co-create

As well as having amazing facilities and people, SUSTech is nestled in one of the most beautiful parts of the city.

During my stay, I partnered with Seungwoo Je and his students to collaborate on some upcoming research. As part of this, I’m working towards making a toolkit for Printegrated Circuits. One of my goals while in Shenzhen was to find partners to help with the manufacturing and distribution process.

This was exactly what Seeed Studio was offering as part of their Co-create Programme. You design a prototype and they provide engineering support to take your project from protype to product. Seeed manage production, distribution, and promotion on their platform.

We had a great initial chat with the Seeed Co-create team on their office’s balcony about the next steps in bringing the Printegrated Circuits project into people’s hands.

A Very Shenzhen Chinese New Year

Shenzhen isn’t really the place to be for the Lunar New Year. Rather suddenly everything shut down: the factories, electronics markets, and even malls went eerily silent. However, pockets of celebration were still dotted around the city including the HQB pedestrianised street, and they did not disappoint!

In Shenzhen, it’s not year of the snake, but year of the cyber-snake!

What did I learn?

Reflecting on my time in Shenzhen, I realise that what I experienced was merely the tip of the iceberg. This vibrant city, with its complex ecosystems of manufacturing and innovation, holds much yet to be explored. My journey has filled me with profound respect for the people of Shenzhen—their remarkable work ethic and their relentless drive to innovate are truly inspiring.

Often, outsiders view Shenzhen as a hub for imitation, a place teeming with replicas and low-cost alternatives. However, my observations have led me to a different conclusion.

In Shenzhen, the act of replication is not just a way to make a fast buck; it is a sophisticated form of learning and innovation, filling every niche of the market. The city thrives on rapid prototyping and direct engagement with materials and machines, transforming electronics manufacturing into an art form, unbounded by the rigid processes that dominate Western engineering practices.

George Bernard Shaw once remarked, “Imitation is not just the sincerest form of flattery—it’s the sincerest form of learning.” Shenzhen embodies this ethos, and has mastered the art of scalable and rapid electronics production. As I return home, I am eager to explore how we can integrate elements of Shenzhen’s dynamic ecosystem into our local practices. My goal is to enable rapid electronics production anywhere, democratising access to the tools needed to solve the biggest problems. It’s our turn to imitate Shenzhen and learn from it!

Acknowledgements

Thanks again to all the wonderful people who made this trip possible, especially Cedric Honnet and Suengwoo Je without whom, I wouldn’t have been able to make this visit. I’ve come back from Shenzhen with a bit Cedric’s infectious curiosity, which throughout the trip displayed itself as he took the time to explain all the interesting things he’d discovered on previous visits, as well as linking me up with people and encouraging me to always delve one level deeper. I also learnt a lot from Suengwoo who has crafted a wonderfully aligned research group at SUSTech, displaying impressive dedication to their craft. It’s not just them though, I’d also like to send some love to all the people who worked in the background to make it run so smoothly. I’m very grateful to the EPSRC-funded pro2 network+ who sponsored the trip and ongoing research collaborations.